1950 + Articles

Articles written about the ship and voyage after 1950.

Articles written about the ship and voyage after 1950.

The English translations of the following original newspaper articles are not a verbatim exact duplication of the Estonian text, but rather a very close English version of the original. Note also, that translated newspaper articles from various sources appeared both shortly before and after the Walnut voyage. Many news articles contain factual inaccuracies, but are presented herein as published and written by their authors.

The Canadian Star Weekly

Author: Walter Kanitz [spelling not clearly visible] - Dated sometime in 1968 ?

In the early morning mist of Dec. 13, 1948, the pilot of a Canadian coast guard plane spotted a small vessel wallowing helplessly in rough seas, 200 miles off Nova Scotia. Unable to make radio contact, he signaled Halifax. A few hours later a cutter came alongside the 600-ton Walnut; a former British minesweeper. An officer went aboard and discovered a waking nightmare. He found 364 passengers -- men, women and children -- crammed into the hold of a ship that had been built originally for a crew of 14. The human sardine can stank abominably. People were stretched out on bunks, on the floor, everywhere. They seemed dead.

The officer climbed back on deck and took a deep gulp of fresh air. "Dead?" he asked the captain. "No," the captain told him, "not dead -- almost."

A tugboat towed the Walnut into Halifax. Ambulances took the passengers and crews to various hospitals. The immigration people hustled to look after the unexpected shipload of new Canadians.

Valdim Tuklerim, today a prosperous real estate operator in Hamilton, Ont. who has changed his name to Val Tukler, confirms what the captain said. He was one of the crew of the Walnut. "A few days longer," he says, "and we would have been dead. All of us." Latvian-born, Val was one of the anxious and miserable group of Latvian, Estonian and Lithuanian refugees who had left the Swedish port of Göteborg on November 11 to sail for "the free, democratic land of Canada." It was the period of the worst mass deportations to Siberia that the population of Latvia, Estonia and Lithuania had experienced in the succession of foreign occupations since 1939, in which Russia had alternated with Germany. To escape this fate thousands had fled to Sweden, where these 364 had banded together to buy the old British mine sweeper from a scrap yard. They saw it as their only hope for freedom, as there were constant rumors that the Russians might invade Sweden.

Twenty years later, Val Tukler's emotions still run high when he recalls their fantastic escape. Middle-aged now, father of two, he was lean and hungry and in his late 20's when he helped organize the voyage. From among Sweden's masses of Baltic refugees they recruited 364 and collected $100,000 to buy and outfit the ship. Most of them handed over all the money they had.

When the Walnut left Göteborg, a final deception was necessary. There had been no money to buy radio equipment, without which Swedish authorities would not let it sail. So Captain August Linde, an Estonian refugee, borrowed the equipment from another ship and once outside Swedish territorial waters returned it to the owner who had escorted them. "I'll find my way to Canada blindfolded," said the captain. And he did.

Photo caption: Twenty years ago next week, 364 Baltic refugees debarked from the Walnut at Halifax. They had crossed the Atlantic without heat, food or radio equipment.

November and December are notoriously bad in the North Atlantic and after a week of 50-foot waves everyone was miserably sick. Living conditions were incredible. There was only three feet of space per couple on each bunk and the bunks were stacked three layers high in a hold 7 feet high. Salt water had spoiled the food. The air stank. Clothing was permanently soaked. Sanitary facilities were almost nonexistent.

But the Walnut plowed on and each day Canada came nearer. The sea poured in with every wave. Then the pumps, working furiously around the clock, broke down. Everyone who could, bailed by hand, nonstop. Finally after three weeks a giant wave swept away all the coal remaining in open bins on deck. Shortly afterwards the engine conked out. For six days and nights the Walnut drifted in the waves, luckily pushed westward by the winds. It was on the morning of the seventh day that the plane spotted the ship -- the 32nd day of the voyage.

As the 20th anniversary of their arrival in Canada approaches, Val Tukler has lost track of almost all his companions in misery on the Atlantic crossing. As far as he knows most of them are safe, sound and prosperous scattered across Canada and the United States. Any who wish to share a reunion-by-mail can write to..... [removed by webmaster - Canadian Star Weekly ceased publication in 1973.]

Nelly Lind's strongest memories of her flight to freedom in Canada aren't about fear.

And they aren't about the huge Atlantic Ocean waves that washed over the deck of the tiny ship, the Walnut, forcing passengers to cling to the railings or be washed overboard.

Lind's strongest memories are of sauerkraut soup.

"There were lots of little worms in it," she says, cringing at the memory 50 years later. "That was something I'll remember always."

The passengers of the Walnut, a former Royal Navy minesweeper, held a reunion this weekend at St. Peter's Estonian Evangelical Lutheran Church on Mount Pleasant Rd. near Eglinton Ave. E.

But the wormy memories didn't hinder the 78-year old woman's appetite during Saturday's festivities, as she enjoyed smoked turkey and kringel, a sweet bread, along with more than a hundred other Walnut passengers and their families.

For Hilya Kuutan, aboard the Walnut as a 12-year-old, her strongest memory is of the pure excitement. "It was an adventure for us. As a child, you were not scared."

The 347 passengers of The Walnut, who braved a month-long voyage to Canada, started their long journey when they fled Estonia for Sweden to escape the Red Army during World War II.

When the war ended, the Soviet government demanded that Sweden return its citizens. In 1948, the refugees watched in horror as fellow Estonians were dragged crying into boats and back to the Soviet Union.

Rather than face the same fate, they decided to flee to Canada.

The journey wasn't easy for most of the passengers.

"I didn't eat for a month, I was so sick," said Lind, who crossed the Atlantic with her husband Tõnis and her sons Tony and Tiit Eric.

The passengers were told before the voyage that they probably wouldn't be allowed into Canada, but they gambled and came anyway. The risk paid off. Parliament created a special exemption to allow them to land on Canadian soil.

"We were really among the first board people," Kuutan said. "It was a refugee boat. We came here illegally. They just didn't call it that."

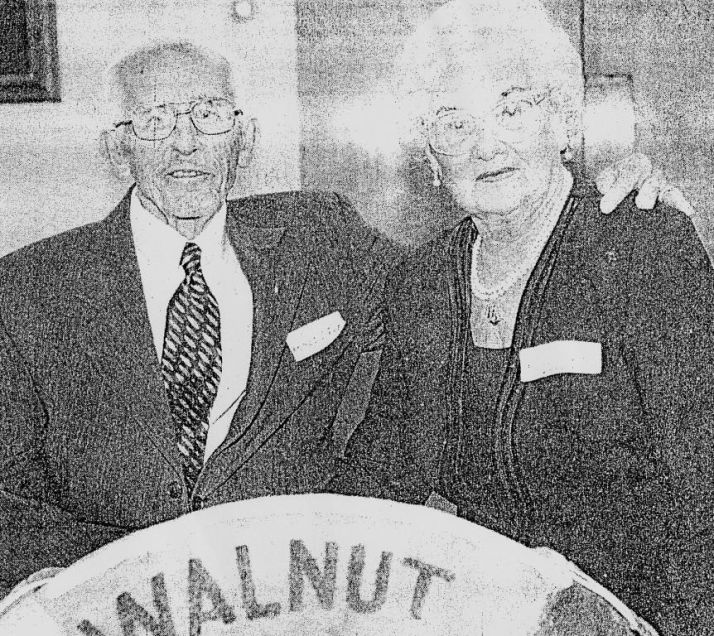

Although Harald Sarg, 93, and his bride of 49 years Helmi, 78, won't call the Walnut a love boat, they did meet on board and were engaged within three weeks of their arrival in the Toronto area. "He figured I was a good-hearted person," Helmi said with a smile.

Sarg made his living as a construction worker while his wife worked in the office at Sears. Like the rest of the Walnut's passengers, they are proud they were able to support themselves without government aid.

Photo caption: Harald Sarg, 93, and his wife Helmi, 78, enjoy the 50th anniversary reunion of passengers who made their way to Canada aboard the Walnut, where the pair met.

Ene Pomerants Johnson remembers lots of crying, but not much else of the voyage. She was just 3. "I was very ill and I didn't eat at all," she recalled. "My mother even said (jokingly) they were going to throw me overboard." Like most of the passengers, her family settled in Ajax.

There are about 10,000 people of Estonian heritage in southern Ontario, possibly the largest Estonian community outside Eastern Europe.

It was worth the ocean waves and the worms in the soup to get here, Kuutan said. "You're part of Canada. There are no regrets."

We are all looking to simplify our lives. For most, that means purging those things that we no longer need. But what about the things that are soaked in memories? The things that we are attached to that remind us of our past and our loved ones? These are the things that transport us to another time. Amongst my keepsakes was the Compania Maritima Walnut S.A. Minute Book. Both my parents came from Sweden to Canada aboard the Walnut. My father was one the one responsible for keeping the ship’s Minutes. The book is a brown, legal-sized bound ledger with lined pages. I am very sentimental. I enjoyed flipping through the pages, reading the entries and imagining the circumstances under which the words on the pages were written. Entries were made in Sweden, aboard the ship and in Canada. It gave me a sort of comfort to run my fingers over the yellowed pages, filled with words written in blue ink.

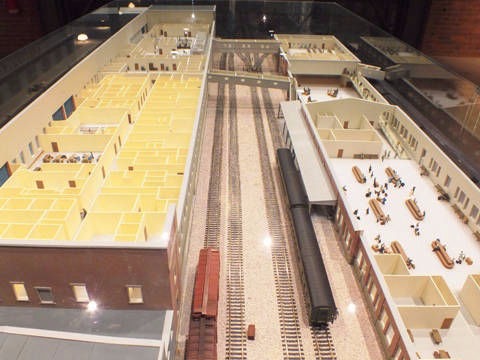

At the same time, my thoughts often turned to Pier 21 in Halifax. It is to this Pier, like so many other immigrant ships, that the Walnut arrived and where its passengers took their first steps to becoming Canadian citizens. Constructed in 1928, the Pier has gone through many upgrades. It originally consisted of a large complex of freight piers, grain elevators, a new train station and a 600-foot, two-story shed. The shed was built of steel truss-work with brick walls and a wooden roof. An area of 221,000 square feet was divided into Piers 20, 21 and 22. It faces a long sea wall.

The Pier operated as an ocean liner terminal and immigration shed from 1938 to 1971. In the decade immediately following the Second World War, Canada received about one and a quarter million immigrants from Europe, most of whom arrived by sea. The newcomers consisted of the dependents of returning Canadian servicemen and people dislocated by the conflict and aftermath in their homelands. Most of them arrived by sea, with Halifax serving as the major port of entry.

The immigration facility on the second floor of the shed at Pier 21, housed the assembly hall for immigrants and held medical and detention quarters. Rail tracks separated the Pier from a brick annex building. Two walkways connected the shed to the annex, the first leading to the Halifax railway station, the second, to which the Walnut passengers were directed, led to the annex building which contained immigration offices, customs, a railway booking office, the Canadian Red Cross and a restaurant.

The Pier has changed since the time the Walnut passengers arrived in 1948. In 1950, a two-story addition was built onto the immigration annex building to accommodate the heavy traffic of postwar European immigration. Since the arrival of the last ship in 1971, the Pier has been used as a training facility for mariners, and as a studio and workshop space for artists in the 1990’s. 1997 saw Pier 21 designated as a National Historic Site of Canada due to its significant role in 20th century immigration to Canada. As cruise ships began to visit the Halifax area, former immigration terminal areas in Sheds 20 and 22 were converted as cruise ship passenger reception and retail spaces.

Above: The deck as Walnut passengers arrived at Pier21 in December 1948. Right: The appearance of the deck as it looks in 2016, a significant part of the museum. New immigrants entered Canada through these doors. This hallway marked the end of their transatlantic journey and the beginning of their new lives in Canada.

After entering the Pier, immigrants had to pass through a series of admission procedures. The newcomers waited in the assembly hall for interviews with immigration officers and had to pass through customs. Some received medical care, while others like the Walnut passengers, were detained.

Below left: Museum replica of assembly hall. Below right: Walkway from shed to annex. In this hallway, immigrants were questioned by immigration and customs officers. (2016)

Pier 21 is the last surviving seaport immigration facility in Canada. Even since my last visit some years ago, the area around the Pier has changed dramatically. There are now many retail shops, cultural organizations and artists’ studios occupying the remainder of the row of piers. Cruise ship visitors are greeted by stalls of vendors displaying Canadian products and tourist merchandise.

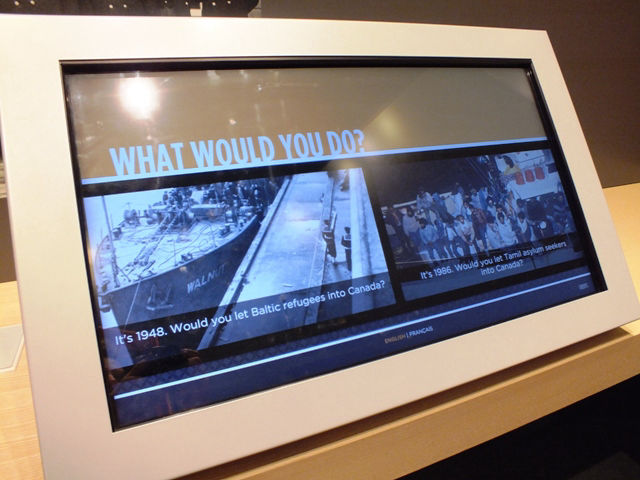

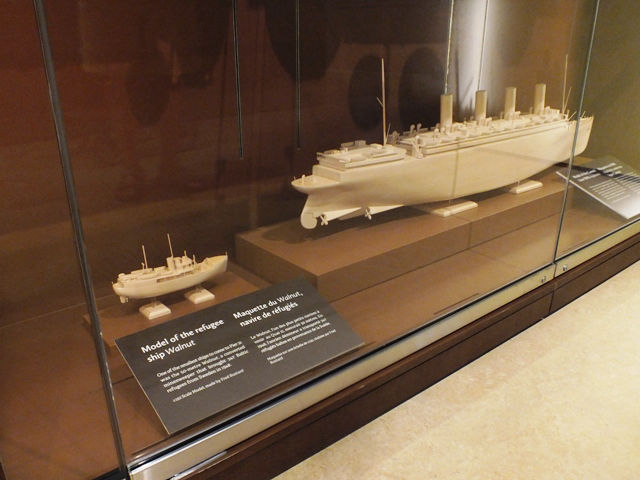

Above: Museum visitors read about the Walnut’s arrival and decide what they would do. Would you let the Baltic refugees into Canada? Asta Piil and Hilja Kuutma’s stories are presented. Right: Models compare the smallest of ships, the Walnut, to the largest to arrive in Halifax .

The Walnut ship’s arrival is prominently included in museum displays and learning activities since it was the tiny ship that changed Canada ’s immigration policies. Its arrival is part of displays and interactive stories. I decided that the place for the Walnut Minute Book belonged here, amongst all the other collected data, letters, images and stories. The Pier 21 museum is used regularly by researchers and aims to provide complete collections of historical data. I contacted the museum and offered to donate the Walnut Minute Book to the museum.

As part of a family vacation, on September 1st, I was due to arrive in Halifax by cruise ship. I got up at 4:30 a.m. to watch as our ship pulled into the Halifax harbour. I wanted to see what my parents would have seen as they made their final landing onto Canadian soil.

The sun had not yet arisen and a heavy fog greeted me that morning as I appeared on the deck. In fact, there was nothing visible at all. I could hear the clanging of the bell buoys and the eerie sighing of the whistle buoys that make a sound much like that when you blow over the top of an empty pop bottle. The ship itself was sounding its fog signal, beeeeohhhh, warning others of its arrival. My emotions overtook me, for I thought about what those Walnut passengers must have been thinking, entering this same harbour almost sixty-eight years ago.

I first met with Jennifer Hevenor, the Collection Manager of the Museum. She was very pleased and excited to receive the Walnut Minute Book as part of the museum collection. All materials that are part of the collection are invaluable cultural resources that help Canadians learn about and engage with the nation’s immigration history. Following the donation, my family and I were treated to a fascinating private tour of the museum with researcher, Jan Raska. I left Halifax that same afternoon, watching as the pier and the outline of the cityscape slowly disappeared into the distance knowing that the story of the Walnut and its archives and artifacts are in the capable hands of the museum’s curators. The material will be protected and cared for by stewards of the collection to further the museum’s mandate to promote an understanding of the breadth of experiences of immigrants to Canada, and their role in the evolution of the country’s culture, economy and way of life. I am satisfied and happy that the Book now has a proper home. My precious keepsake and memories can be shared with so many others.