Service Aboard HMS Walnut

What did the Walnut ship do before her humanitarian role? Tom McCabe shares his memoirs serving aboard the Walnut during WWII.

What did the Walnut ship do before her humanitarian role? Tom McCabe shares his memoirs serving aboard the Walnut during WWII.

Who was Tom McCabe?

Tom McCabe’s father was a policeman in a tough mining town called Skinningrove. Tom also joined the Police and served in Southbank in Middlesbrough where he met his wife, Catherine. After WWII he resumed his Police service and became a Chief Inspector, before taking charge of security at a very large industrial facility near Middlesbrough, ICI Wilton Works. He retired in Whitby, home of Captain Cook. He is buried with his wife and other members of their family in Eston.

It is 1942 – Along with other policemen from England, Tom McCabe finds himself in the Seaman Branch of the Royal Navy. He goes through 12 weeks of rigorous training including seamanship. A call goes out for volunteers for various branches of the Service including Minesweepers and McCabe volunteers for the “Sweepers”. His request for a job on a minesweeper goes through in mid-November 1942. He serves on several ships and is then sent aboard the Walnut.

Tom’s grandson, Paul McCabe, proudly shares and an extract from his grandfather’s memoirs from his time aboard the Walnut.

We thank Paul for sharing his grandfather's recollections and images with us.

All text is subject to copyright © Paul McCabe 2020, not to be reproduced in full or in part in any form, subject to permission.

Text, paragraphing, etc. reproduced exactly as written by Tom McCabe. The ship photographs were found in his estate and have been added. Several "Notes" have been added to clarify terms that may not be familiar to the non-seafering reader.

Allocated as a relief to HMS Walnut

Back again to 1942, the minesweeper “Unst” was still at sea and the day after I had been on board Nelson’s “Victory” I was brought back to reality – HMS 'Walnut' another of the 'Bay' or 'Tree' class corvette type minesweepers was due to sail that afternoon with a convoy and they were shorthanded so I was sent on board as a relief for two weeks – and I remained on this ship for 2½ years!

Junior ordinary seaman

I was allocated to the seamens' fo’ castle mess and being a junior ordinary seaman – in fact the most junior man aboard the ship – I had to sling my hammock above one of the long narrow mess tables when meals were over for the day. I will try now to describe generally the routine and day to day life on board one of these types of vessel. Immediately on coming aboard the 'Walnut' I noticed from the brass plate attached to the front of the wheel-house that the ship had been built by Smiths Dock & Co. Ltd. at South Bank-on-Tees in 1939 and the small girder across the mess-deck had been rolled by the 'Skinningrove Iron & Steel Co.' So I suppose it was only natural that I soon made myself at home on board especially when I found that practically all the angles, beams etc. had originated from the 'Grove'. There were about 22 of us accommodated in this small mess-deck which really was at the 'sharp end'. There were two leading seamen in the mess with us and they with the more senior able-bodied seamen occupied the folding bed-bunks which were in two tiers at each side of the ship. Being tied up at the Buoys in Portsmouth Harbour my first task was the one apparently always given to the most junior rating – the chain locker! I was shown the entrance to the chain locker by Punch Caddy, our senior leading seaman and a veteran from the 1914-18 War. The entrance was in the seamens’ mess and consisted of an elliptical plate held by nuts and bolts and it led to a small hold in the forward bowels of the ship. “I’ll never get through that small hatch” I said. “You will” replied Punch Caddy. “Blokes twice your size have got through – just put your hands and arms above your head and let yourself go slowly down the ladder.” When I was through the oval shaped hatch and down the iron steps the windlass [Note 1] on the f’ castle head above us suddenly started up and the anchor cable started to come tumbling down inside one of the large hawse pipes [Note 2] which ran vertically through the seamens’ mess deck and then the cable settled into a sort of giant box with high sides made of thick planks of wood. Punch the leading seaman shouted further instructions “Pull the anchor cable towards you so that its evenly distributed and doesn’t get snarled up [in] the hawse pipe there’s miles of it to come in yet.” Although others were hosing the filthy mud off the cable as it was hauled up from the harbour bed there was still lots of mud clinging to the cable links and as I pulled them through the links rattled my finger ends but at last it was safely housed and I heard the ships [sic] engines start up – we were off, but Punch was waiting for me I was required for the fo’ castle saluting party – “At the double saluting parties fall in”! Our saluting party consisted of half a dozen matelots lined up on the forepeak and there was a similar number outside the galley aft near the great winch. As we went down the harbour and approached the 'Victory' we were piped to attention by the officer of the watch who saluted from the bridge until our salute was acknowledged from the Commander-in-Chief on board the 'Victory'. We were then stood at ease, passed HMS 'Vernon' another shore establishment then as we approached HMS 'Dolphin' the submarine base at the entrance to Portsmouth Harbour we again went through the saluting procedure and were shortly afterwards dismissed – I believe at Spit. No.5 Buoy?

Spithead and Gun Drill

As we approached the Boom Defence ships at Spithead the Duty Watch were ordered to close up the guns. I was on watch with the gun-layer on the 12 pounder and while daylight lasted, with our full guns crew, we practised loading and reloading this gun until I was sure we could have done it blindfolded. The twin .5 Vickers Machine gun [Note 3] situated above the galley was also closed up for the watches at sea. Meanwhile the convoy of merchant ships, mostly colliers [Note 4], small tankers and other small coasters laden with general cargo all no doubt essential to the war effort were assembling in the Solent and at Spithead ready for the trip through the Straits of Dover. It was about dusk when we set off turning left or rather to Port at the Nab Tower having passed the sort of 'Plum Pudding' Forts also known as 'Palmerstons Follies' apparently built during that politician’s term of office to repel the French but were never needed! Having turned the convoy took a bit of time getting their stations back to the satisfaction of the Convoy Commodore which reminds me of a later convoy at the same stage when our Captain a strict disciplinarian but a very good officer was having some trouble marshalling the merchant ships and in particular with one tramp steamer which was out of position so much so that at one time the steamer and 'Walnut' had got rather close together and our C.O. blew two blasts on the siren and announced on our very efficient loud hailer “I am turning to starboard” and directly to the wayward vessel “What are you doing?” Back came the devastating reply, from a scruffily dressed Merchant Navy Captain with a battered hand megaphone. “Do you want all the eeffing English Channel?” There was a deadly hush and we could see our Captain was absolutely furious, but there would be time for him to cool down before the next meeting of convoy captains ashore!.

Sweeping in front of the convoy

It emerged as we went along that the Minesweepers [sic] task was to sweep directly in front of the convoys. There were at least 8 of this class of ‘Sweeper’ based at Portsmouth. They were split into two flotillas and at that particular time the ‘Walnut’ and the ‘Bay’ were the two flotilla leaders – as a rule travelling in opposite directions about once every 7 or 8 days with a convoy behind them. Others of the Tree Class sweepers that I remember were the Blackthorn; Acacia and the ill-fated ‘Pine’. The ‘Unst’ was one of a very similar class and named after the Western Isles and was working with us. Usually two ‘sweepers would be sweeping in front of the convoy and the others acting as convoy escorts all our endeavours being directed to seeing the convoys safely through the English Channel including the Dover Straits. Seemingly our small minesweepers didn’t carry sufficient crew to cover 2 hours on watch followed by 4 hours watch below so we had to do 4 hours on watch and 4 hours off. It wasn’t so bad in daylight hours when there was the distraction of the merchant ships to scrutinise and the fighter aircraft circling round and round the convoy but at night in Winter 4 hours seemed endless. More on this subject later!

‘Out sweep’ and dealing with floating mines etc.

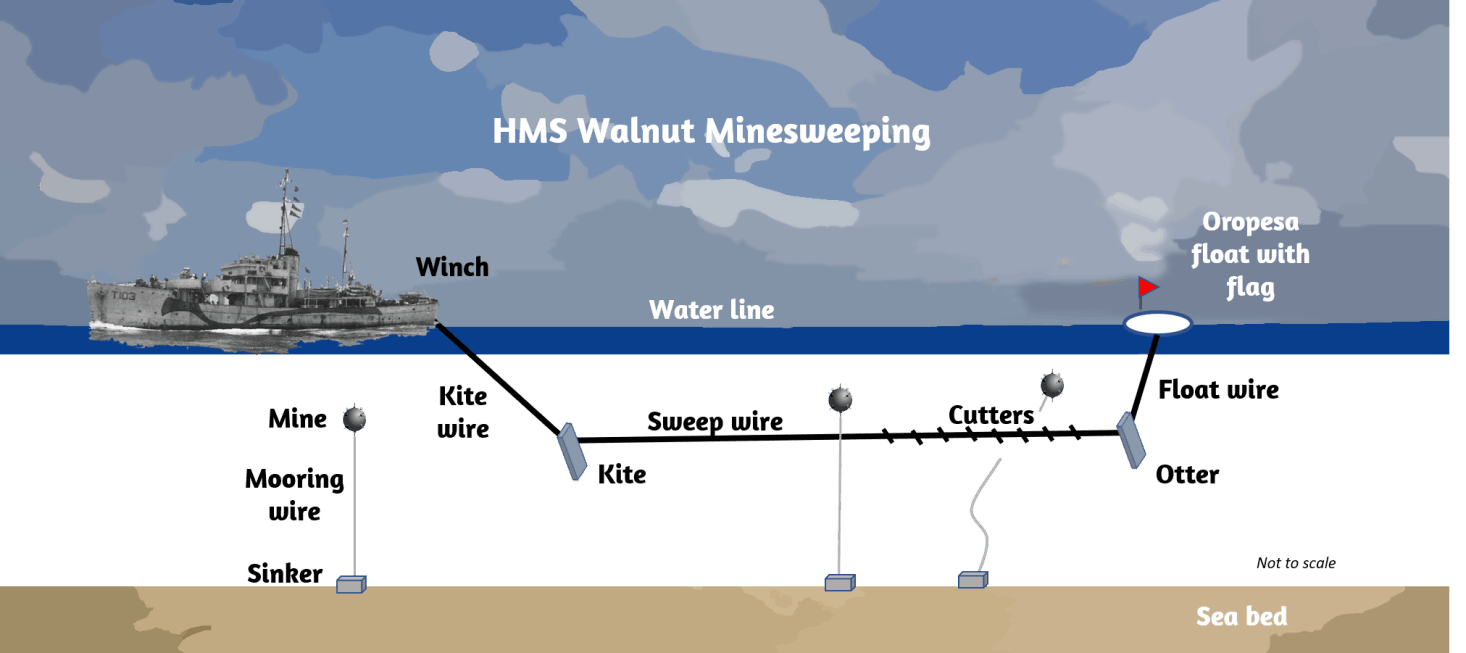

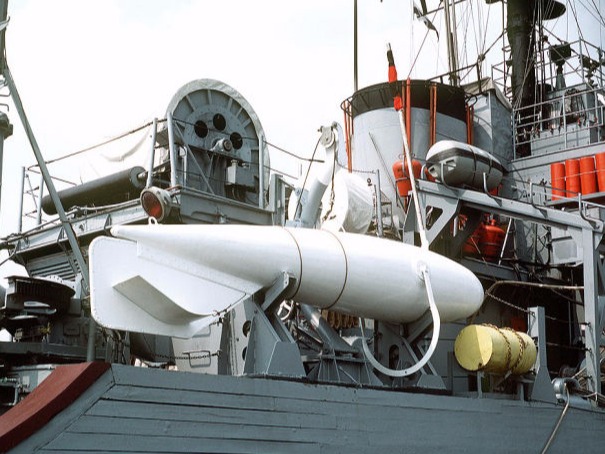

If it was the ‘Walnut’s’ turn to sweep, on the order “Out Sweep” being given the great Tunney Fish like Orepesa [sic] Float [Note 5] was streamed and then tethered with a steel fluted frame known as a ‘Kite’ which at a guess weighed about 3cwt and to which steel hawsers were attached with a patent cutting device to sever enemy mines from their anchors so that they would drift clear of the ships in convoy. Quite often mines did surface and were either sunk or detonated by gunfire from our ships. Normally also there was one Hunt class destroyer forming the main unit of the escort and as I’ve just mentioned fighter aircraft cover during daylight hours. There was a marked and swept channel for the convoys through the English Channel but the Germans knew all about the convoys of course and kept laying more mines and had been known to have their “E” Boats waiting for a convoy with engines switched off in the swept channel so that our ADSIC device couldn’t detect them.

(Image below created and added by Walnut website)

"The “O” type of minesweeping, known by it’s Oropesa float, is a single ship technique illustrated above. This technique uses the same type of “kite” or “otter” as the “A” sweep to regulate the depth of the sweep. The Oropesa float is used to take the sweep out from directly astern of the minesweeper to create a sweeping arc. As with the other systems, the sweep cable has a serrated cutting edge that cuts the mine mooring cable, causing the mine to surface where it can be destroyed. "

We would like to acknowledge ”Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, Manual of Seamanship, Vol. II, 1952” as the source of the information. “The Fact Sheet” from which the above minesweeping description was obtained was prepared by Mike Braham for the Friends of the Canadian War Museum. Used with permission.

Passage through the Dover Strait

The four hour gun watches in Winter with little or no shelter from the elements were no picnic, ten minutes seemed like an hour. No smoking was allowed on watch after dark, everyone was tense and eyes straining on the lookout for any sign of the enemy. The channel convoys were timed to arrive in the vicinity of Dungeness in order to go through the Dover Strait after dark. As we approached the Strait the ‘Watch Below’ were called to haul in the sweep and then at maximum revs we hurried through the narrow strip of water. On the seaward side I could see that enemy searchlights were sweeping the sea then great flashes could be seen apparently from the heavy German cross channel guns – “count twenty” (or was it thirty) someone shouted from the bridge and the “Line down” – we did but as often happened on future convoys we were fired at but saw no sign of the end product. Then we were off Deal and going through a veritable graveyard of ships on the Goodwin Sands, some of these wrecks of merchant ships had bridge and masts exposed all the time, others were showing only at low tide. At night it was even more like a churchyard with bell buoys ringing out their warning and green wreck buoy marker lights dotted all over the place. During day hours on subsequent convoys we often had some firing practice especially with the Oerlikon guns with the exposed wrecks’ masts as targets.

Journey’s end at Gillingham Reach

At last we reached Sheerness and ‘Trot’ boats came out to take the barrage balloons from the escort vessels, the convoy dispersed most going up the Thames. Walnut and the other sweepers continued up the Medway to Gillingham Reach near Chatham Dockyard where we tied up at the Buoys for 36 hours. On my first trip except for one ‘Action Stations’ alarm when star shells and tracer bullets could be seen in the distance and a loud rumble of heavier gun fire nothing untoward occurred and the “Stand Down” had soon come from the bridge.

Return journey to Portsmouth

Then 36 hours later we were ready for departure once more. Convoy assembling in Thames Estuary – again mainly colliers laden with coals from Newcastle, small tankers carrying petrol and oil, other coasters carrying steel and general cargo. As we approached Goodwin Sands again we had an even better view of the scores of wrecks littering the approaches to the Thames Estuary. I gathered from other crew members that many of these wrecks had been victims of German magnetic mines before the ‘Degausing Antidote’ [Note 6] had been discovered and fitted to all our Naval and Merchant vessels. Then we were almost to the Straits again – in darkness for the hurried passage!. On a later trip during the Summer months with wind and tide behind us we had got too far ahead of the convoy and were almost to Dover and it was still broad daylight. Heliograph signals were flashing a message “Get to Hell out of it” which we promptly did. One bridge look-out swore that with his binoculars he could tell the time on Calais Town Clock!. On the return trip we followed the same watch procedure 4 hours on and 4 hours off. I didn’t altogether go bundle on the first watch midnight to 4am! By the time I got thawed out and into my hammock it was time to go back on watch 8am to 12 noon! On some trips we also got the shrill ‘Action Stations’ alarm bell just after going off watch and we were back on the guns for anything from half an hour to one and a half hours. In addition all hands off watch had to turn out for “In Sweep” and “Out Sweep” calls when the cable had to be winched in and the great steel kites and Crepesa float hauled on board. From the time I joined the ‘Walnut’ I never ceased to marvel at the wonderful skills and seamanship of those from the peacetime trawler fleets who were serving with us. There was Leading Seaman George Thurston from Hull; Bill Bruce from Lerwick in the Shetlands; Jimmy Reid from Buckie; Punch Caddy from Weymouth; Jim Marchant from Brighton and another who I only ever knew as ‘Grimmy’ or “GY”. These were all quite at home in a seaway when the deck was awash and steel hawsers that could cut a chap in half were flying about all over the stern and the winch in the inky blackness at night. George Thurston operated the giant winch and was in general charge of the sweeping gear and he was also, with two ratings, the ASDIC (anti submarine listening gear) branch head on board and was responsible for maintaining and setting detonators on the rows of depth charges we carried on board.

Back in Portsmouth Harbour

Marvellous when out of the sea emerged the Isle of Wight and the Nab Tower and we were back saluting the ‘Dolphin’ and HMS Victory and then we were tied up alongside the quay directly opposite the Base ship ‘Marshal Soutl’ once more. With being senior ship we got alongside the quay, the next ship in Captain seniority was next one out alongside us and so on but as a rule the most junior ship(s) had to tie up at the buoys in the middle of the harbour. This was not so convenient as all stores had then to be ferried by ship’s small boat. About one year later our Captain Lieutenant Commander Hamilton-Adams received further promotion and moved on to a Fleet Sweeper and so ‘Walnut’ became junior ship and we had to stay that way for long enough!.

Gunnery Course

As soon as we tied up in harbour our tasks for the following day appeared in the ‘Night Order Book’. This time I was detailed for a 14 day gunnery course so it was back to the ‘Marshal Soult’ for another stint but not quite such a ‘green horn’ this time. The course was uneventful and I was glad to get back on board the ‘Walnut’ again. In the following few months as soon as we entered Portsmouth Harbour all gunners were sent on one day practice shoots to Bognor Regis at the seaward end of the Pier firing at the target sleeve towed by a fighter aircraft, this was a regular chore, then there were visits to the Ack-Ack [Note 7] Dome Teacher Training which simulated attacking dive bombers or instructional training films for Naval gunnery or practise shoots at sea with a small drifter towing a raft with the target set up on the raft – the old drill came in handy “By percussion fire a tube ---------------“. I remember one very cold and frosty November morning four of us were due at Whale Island for yet more gunnery training. Whale Island was directly opposite the quay where our ships normally berthed so we caught the ‘Trot’ boat passing the old Royal Yacht “Victoria and Albert” tied up at the Buoys nearby – she looked very much as we got close by as though she had seen better days with much of the visible gold paintwork well tarnished. We were dressed in long watch coats with collars turned up on account of the cold as we landed on the catamaran with hands thrust so deep into pockets and as we were strolling past a sort of Sentry Box there was a shout and out of the Sentry Box shot a Gunnery Warrant Officer (Drill Pig) in full uniform complete with black leather gaiters and all “Where the hell do you think you are going ---------? I’ll take you to bits to see what makes you tick -------” he then proceeded to give us 5 minutes drill at the double -----” When you come here to Whale Island” he said “You don’t walk anywhere, we don’t expect you to run ---- you bloodywell fly”! That was our first taste of Whale Island, we didn’t go much on it then but it is nice to look back on from this distance in time!.

Starboard Oerlikon Gunner

We refitted at Southampton and had posh Oerlikon Gun Turrets [Note 8] fitted at the port and starboard side almost amidships and between the Bridge and the 12 Pounder Platform. I was appointed as the official Starboard Oerlikon Gunner and Ted Grainger (Tich) the Port Oerlikon Gunner. We were all posh on the new guns and each had a telephone direct to the Bridge and we carried our 4 hour sea watches in turn on the Oerlikon Guns as soon as we reached the Boom Defence ships at Spithead it was “Starboard Oerlikon to Bridge ------” Starboard Oerlikon closed up Sir.” Our Captain regularly put us through our gunnery drill and one fine afternoon on convoy he approached Ted Grainger and I saying that if we went into action at night we would most likely have to re-load the Oerlikon Guns with a magazine pan weighing 56 lbs in the darkness so he proposed to blindfold each of us in turn and time us on his stop-watch to see how long we took to unload a pan of ammunition and to re-load with another from the ammunition locker at the base of the turret. He took poor Tich Grainger first and blindfolded him with a black silk scarf and he took about 2 minutes “No bloody good – too slow you’ll have to have much more practice.” Then it was my turn but with having a fairly large nose the Captain didn’t make a very good job of blacking me out and when he had tied the scarf over my eyes and knotted the ends at the back of my head there remained a small narrow aperture alongside my nose through which I could just see the breech of the gun, the ammunition pan and the locker. When he said “Right off you go” I quickly whipped out the pan from the breech, grabbed another from the ammunition locker and straight into the breech the pan immediately clicking into the retaining apertures. “Fantastic, unbelievable, it’s a record” he went on. In fact it was much too good I’d made a rod for my own back. Unknown to us he’d had all the ships in his flotilla doing the same exercise and when he got back to Pompey had had his meeting with his brother Captains and when the exercise with the Oerlikons was discussed and the timings were produced the others absolutely refused to believe so they all trooped onto the “Walnut”! “McCabe” says the Captain “You must do it once more to convince them.” This time the neutral officer blacking me out made a right good job of it – the counting started “Twenty seconds – thirty seconds – forty ------ one minute ------ two minutes ----- three minutes. “Cor you’ve let me down” says the Captain “Get a decent bloody watch next time” says one of the other C.O.’s. “Serves you bloody well right” says little Tich Grainger “It never pays to be too bloody good in the Andrew Lofty, try to remember that!”

Rabbits in the Navy

I suppose it was inevitable that sailors would store up their cigarettes and rum ration for when the time came to go on leave. Rabbits as every matelot called them made life worth living on board a small ship on the other hand going home for ‘boiler clean’ leave was a cherished privilege and to be caught smuggling rum cigarettes or tobacco meant certain detention for ratings and demotion for senior NCO’s. Incidentally one of our Petty Officers was caught by Customs Officers with a very small amount of rum in a flask (1/3 of bottle size) and our ship was placed under punishment for 3 months and the PO was demoted. This meant that the crew of the ship lost the neat rum privilege for small Naval ships and we had to have two tots of water added to the one tot of rum for the next 3 months. This was indeed sacrilege to most crew members but on the first day ‘Wilf’ the Leading Cook who lived for his rum put his pint mug on the table in the P.O.’s Mess, with Jimmy-the-one (First Lieutenant) in attendance. Paddy McGee the Coxswain poured a tot of neat rum into his mug and as Paddy reached for the jug of water Wilf the cook up with his mug swallowed the rum and putting his empty mug back on the table said “I’ll take the two tots of water now.” That was the end of that on each future day for the specified period the jugs of water and rum were mixed together in a larger vessel before being dispensed!.

Duty free allowances

Whilst still on the subject of duty free goods – the Ship’s Canteen opened on board every other day and we could purchase duty free cigarettes and tobacco. Twenty of the popular brands of cigarettes such as Capstan, Players or Senior Service cost six pence (old money 240 pence to the £1.) 20 Kingsize cigarettes seven pence and Twenty (ships) Woodbines which were as large as Capstan fourpence halfpenny. Also on seagoing ships we could draw in addition once per month one pound of tinned (Tickler) shag tobacco for rolling cigarettes or one pound weight of actual tobacco leaves for rolling a prik of plug pipe tobacco for 13 pence. By the way it was an education seeing an old sweat rolling a prik of leaves with added rum in a canvas square and bound together with yards of spun-yarn. With concessions like these there was a very strong temptation to take a bottle of rum or some cigarettes and baccy to one’s dear old Dad at home paying through the nose for his smokes and drinks to help pay for the “War Effort. One of the Minesweepers in our Flotilla was due for boiler clean after one more convoy and the story went the rounds that some members of the crew had met ashore in a pub near the dockyard Gates a member of the Royal Marine Police who had offered to get all their “rabbits” out of the dockyard for them if they put all the contraband in a suitcase the night before leave was due [and] he would collect the suitcase and have same waiting for them in a specified bar the following lunchtime. The RMP collected the suitcase from the ship in due course and that was the last they saw of him or their “rabbits”. Of course no one could make an official complaint but if any of the victims had met up with him I’m sure they would have dealt with him in an appropriate manner!.

The matelot and the dock gate policeman

Another story going the rounds of our ships at about the same time, although I can’t vouch for this one, was of the matelot going up to the RMP at the Dock Gates asking if he could bring his “rabbits” through the gates (giving a specified cut to the RMP) at a certain time the following day. This was agreed and the next day Jack was hauled inside the Gatehouse and his gear was turned inside out but there was no trace of the cigarettes, baccy or rum. “Where is the Stuff?” asked the RMP. “You’re too late” said Jack “I had it with me last night.”

Walnut crew from all parts of U.K.

I suppose on a small ship of this size with thirty odd crew almost living on top of each other day in and day out temper did occasionally get a bit frayed but as a rule there were not many idle hours in port or at sea. The first Chief Engineer that I had served with was CPO Jack Hearty, an Irishman from Northern Ireland and a staunch R.C.. The Coxswain was Paddy McGee also from Northern Ireland and a Protestant but they were the best of friends. Then there was PO Ben Cullen and PO Jock Ferguson both engine room staff. (I was particularly friendly with Jock Ferguson and used to go ashore with him. He was a Glaswegian had no hair on his head but his chest and back were like coconut matting, and he was as strong as a bull. When due for refit in Southampton a steam pipe burst and scalded him badly on his neck and chest. I went with him to hospital but he absolutely refused to stay (he would have had no option if it had been a Naval unit) and he went off on 14 days leave that afternoon swathed in bandages and he came back on time.) Mostly our stokers were Glaswegians or Welshmen from South Wales and we had a fair sprinkling of these amongst the seamen. One Taffy Davies had been with the ‘Walnut’ from the time she commissioned on the Tees in 1940 and was based for a while at Hartlepool. Another seaman Jack Jones (painter & sign writer in civilian life) had also been with the ‘Walnut’ since the early days. They used to tell us of the early days with the first Captain who was a New Zealander, apparently his personal steward had been helping himself to a glass of wardroom whisky when he heard the Cap’n coming down the steps of the companionway and he just had time to hide the whisky bottle behind a large framed photograph standing on a sort of sideboard. The steward thought he was away with it until the Captain poked his head into the pantry saying “I don’t mind you drinking my bloody whisky Briggs but please put the bloody cork back when you are finished”! But now back to Pompey in 1943 ------------

Divine Service in harbour

If it was Sunday and we were in harbour at Portsmouth there was a Church of England Chapel in a Nissen Hut on the Quayside but there was no RC Chapel in the Dockyard and I went with Jack Hearty a couple of times to the RC Church outside the Gates of the City. He knew the drill and obtained a pass to get us through the Gates – after the Service a couple of quick pints and back on board. As time went on Jack Hearty left for promotion to Warrant Officer and I continued going to church as and when possible. I suppose it was only human nature that others on board got a ‘”Whiff of the Trifle’ as someone referred to the smell of beer and discovered that it was necessary to go into the City for their particular service, notably Church of Scotland and Presbyterians, so we used to meet afterwards in the little bar outside the Unicorn Gate. The next time I went for a Dock Yard Gate Pass, Jimmy-the-One (First Lieutenant) says to me “McCabe were you a policeman or a parson in Civvie Street? Before I could reply he said “I suppose you know you have converted half this bloody ship’s company!”

Sleeping through the Din

The monotony of the convoy run went on week in, week out, with scares every now and again from Enemy “E” boats, enemy aircraft, loud bangs in the night, star shells, tracers but nothing very serious up to now. We had another short refit at Southampton and came back fully refreshed. We dropped anchor at Spithead and all hands were ordered to muster on the well-deck. On re-commissioning after refit our Captain read the Articles of War ------ ‘Any man sleeping on his watch shall suffer death ---------’ A couple of days later we were back on the convoy run and were watch below 12 midnight to 4am. By this time I had graduated to a bunk – the top bunk on the port side right for’ard, and at sea we just laid on top of the canvas bed cover. I was in a deep sleep and was roused by the “Action Stations” Bell, a mad scramble up the stairway from the mess-deck and onto the Starboard Oerlikon – telephoned Bridge – “Starboard Oerlikon closed up Sir.” “Very good” came the reply. Twenty minutes or so later we got the “Stand Down” message. On returning to the f’ castle mess-deck I heard someone remark “I’m glad it didn’t last as long as the last one.”? It transpired that I had slept through a previous actions stations alarm bell when apparently there had been some activity from “E” Boats. In the excitement on the Bridge no one had rumbled that Starboard Oerlikon hadn’t reported “Closed Up”. I was very fortunate indeed that no one had missed me and I resolved to try, if I possibly could, to sleep a little less soundly and to have one of my pals give me a thump when the alarm went. There actually had been another incident not long before which had worried me quite a lot. We were on convoy and the Port anchor just above where I was off watch and sleeping broke away from its tether or housing and a considerable amount of anchor cable ran through the hawse pipe apparently with a hell of a clatter but I never heard a thing!.

Storm in the Channel

It was about this time that we ran into a rare old Channel storm. We were not long out of Portsmouth when the storm blew up rather suddenly with giant waves in no time at all. A large steel cask full of very strong concentrated disinfectant stored in the forepeak just above the seamen’s mess-deck had broken loose and as it topped over the bung came out and most of the contents streamed down into the seamen’s Mess. The stench was nauseating and overpowering and it took weeks to get rid of the smell. Most of us would have been sea-sick anyhow – I know that for once I was glad to get out of the Mess and on watch 8am – 12 noon – it was a cross sea and the ship was rolling badly. One minute it seemed from the starboard Oerlikon turret that I could have put my hand in the water, the next I was up sky-high and my opposite number was down near the water on the Port side. I remember the Leading Seaman Punch Caddy and the other old sweats looking very worried indeed and I overheard Punch saying “There could be some bloody sea running when we get round Beachy Head!” He was right of course – the waves seemed twice as big, then they were worried about the new RNVR Officer’s qualification for seamanship and would have liked to face the storm head-on rather than shipping seas broadside on to them remarking that all these corvette type ships had flat bottoms. When I went off watch what with the ship rolling alarmingly – at times it seemed to hesitate and I wondered if it would go back again, then the stench of the disinfectant, seawater in the mess, broken pots everywhere, mess stove long since out and most of us sea-sick, then Geordie the Assistant Cook shouted down the vent that the Galley fires were also out and that there would be no hot food ---------- a string of oaths were sent in his direction but I suspected that if the others felt anything like I did the last thing they were interested in was food!. I was glad to reach Gillingham after that trip and decided as it was my watch ashore to spend the night in the Salvation Army Hostel in Chatham. As I got off the Liberty Boat and was walking up the road from the landing – the road seemed to be still moving – Apparently I still hadn’t got my sea legs. I stayed the night in a tiny cubicle at a cost of one shilling – the bed was clean and comfortable but I was disturbed about 3am – police accompanied by witnesses looking for a sailor who had allegedly stabbed a marine in a local pub. Suddenly the door flew open, covers were pulled off my face, a torch shone in my face. “Is that him?” someone asked. “No” and off they trooped next door and I was off to sleep again.

Volunteers required for Regulating Branch

Back on board next day and much rested after my night ashore. The sea was much calmer but the smell of disinfectant was everywhere. It was about this time that I happened to see an AFO (Admiralty Fleet Order) that had originated many months previously asking all regular policemen serving in the Navy, provided they had completed six months service at sea, to volunteer for transfer to the Regulating Branch of the Service where they were urgently required. I put my application in but the Captain said that now [that] I was a qualified gunner I was urgently required on board the “Walnut”. He also handed me my Silver Minesweeping/Anti Submarine badge, awarded for six months service on a seagoing minesweeper!.

HMS ‘Pine’ torpedoed and sunk on convoy duty

More convoys, mainly uneventful apart from the odd storm, and then tragedy for one of our flotilla, the minesweeper ‘Pine’. We were in company with ‘Pine’ when we got the alarm during the night when we were almost on the last lap to Portsmouth. ‘Action Stations’ the usual star shell, tracers and very loud bangs and flashes. Then there were a couple of terrific flashes and it was rumoured that two small tankers in the convoy had vanished in them, more flashes and the ‘Pine’ was hit and blown clean in half by a torpedo – the stern half remained afloat – the rest had just disappeared. A few survivors, including two officers, were eventually fished out of the water and shortly afterwards they went back on board to try and salvage the stern half of their ship. They managed to get it taken in tow but a couple of hours later it also sank without warning and the survivors had to swim for it once again! The culprits had been “E” [Note 9] boats on a pitch dark night lying in wait in the swept channel with their engines switched off. We had regularly been laid alongside the ‘Pine’ in harbour and we knew most of those lost fairly well so it came as a great shock to all of us.

Acting as torpedo screen for cruisers

A couple of times on returning to Portsmouth we were ordered, along with two others ships from our flotilla, to act as [a] torpedo screen for County Class Cruisers. This meant the three of us minesweepers tying up stem to stern alongside the exposed side of the cruisers. I believe the ‘Glasgow’ was the first one just back from America. Another was either the ‘Belfast’ or 'Birmingham’. It made sense to write off our humble minesweepers I suppose rather than risk a very modern cruiser. An unexpected bonus for us was that when their Canteen opened we were all invited to shop for fruit (bananas & pineapples) and other delicacies (including fully fashioned silk stockings) not seen in the U.K. for the duration of the War.

Working party to Southampton – and strange vessels

Next several of us were sent, while our ship was under repair, as part of a working party to Southampton to assist in getting some strange looking vessels out of the K.G.V. Dock. The concrete ’mulberrys’ [Note 10] were being built on peace in Portsmouth Dockyard but at that time we hadn’t a clue what they were being used for. The first American Landing Craft to enter Portsmouth Harbour was in a dry dock near where ‘Walnut’ was lying. It was one of those used in the North African Landings and sent on to the U.K. for repairs to damage sustained. We got to know several of the crew really well, they were very, very partial to neat rum and would trade practically anything in exchange for just ‘sippers’ let alone a whole ‘Tot’. One of these Yanks gave me his copy of the booklet which advised them how to handle the British saying the Brits. were naturally reserved especially on buses and trains and went on something like this ‘--------- they have a magnificent history – ruled the seas for almost the whole of the 19th century and not by accident is it that the British flag is flying in all four quarters of the globe and the English language spoken on every continent --------‘. Unfortunately I either lost it or had it stolen from my kit before I was demobbed! [Note 11]

‘Walnut’ recalled to salute correctly

Another short refit at Thorneycrofts, Southampton for new equipment to be fitted, then back on convoy. It seemed obvious that the long awaited ‘Second Front’ could not be long delayed. Southampton was full of Americans, they were under canvas in the parks and seemingly everywhere else. The pubs were bursting at the seams but when they had any beer to sell there were no drinking glasses available so the kids were selling empty jam-jars and milk bottles at 3d and 5d a time (Talk about a nation of shopkeepers!) Then nowadays there were the big ships everywhere, battlewagons – the lot, before we had seldom seen this type of ship in the Channel. On the way back from Southampton we were nipping along the Solent towards Spithead when we came upon the old battleship “Warspite” lying at anchor. Suddenly the signal lights started to flash – we were being recalled to salute the ‘Flag Officer’ correctly!.

Fun with the new Chief Engineer

As I mentioned earlier Jack Hearty had gone but before leaving he was award the DSM and Jack Jones, the ship’s painter and one other seaman were mentioned in dispatches. The new Chief Engineer was a jovial soul and he was from the Grimsby area but again I cannot recall his surname. However he had a large beard and his main hobby was fishing from the F’ castle head in harbour or whilst at anchor. During the summer-time we could often see his fishing line directly in front of a porthole in the seamen’s mess deck and the temptation to tug the line was irresistible. With the inward curve of the ship’s bows he had no idea what was happening and would vividly describe the way the fish were biting to anyone who would listen. He loved a good argument and with his bunk in the petty Officers’ Mess directly below a deck-vent, I suppose again that it was inevitable that when we were washing the decks of a morning the hosepipe slipped and quite a drop of water went into the vent. I can see the Chief now bellowing with rage stood [sic] at the top of the companionway his beard glistening with water, cursing us and threatening dire consequence – but he had the last laugh he grabbed the hose-pipe and dowsed us all well and truly ‘so that’ he said ‘I can be sure I’ve got the right one’! We certainly had a happy ship’s company.

Second Front opens

Small wooden ‘Brooklyn Yard – Minesweepers’ BYMS for short were appearing by the score to detonate the magnetic mines expected to be encountered when the assault was made on the French Coast to open the Second Front. Meanwhile we were given different tasks still in the channel but no longer on Channel Convoys. For a brief period we were working far out in the Channel with the minelayer ‘Plover’ and then we were engaged in laying Dan (marker} Buoys. We came back to our anchorage off Bembridge, Isle-of-White each evening and each time we saw more and more large landing craft assembled. Then there were both Naval and Merchant ships everywhere of all shapes and sizes and suddenly the second front was a reality at last. An R.C. Padre came aboard whilst we were at anchor to hear confessions and give us Holy Communion so the R.C.’s (only about 4 of us) were told to muster at the First Lieutenants [sic] cabin. I went in first whilst Grimmy and the other two waited outside the door which was closed. When I came out ‘Grimmy’ pointed to the ventilation flutes on the door and said “Cor Mac I wouldn’t be you for anything I heard all you said through the vents!” At first in the very stormy weather we were not used to sweep [sic] mines but to retrieve small landing craft and barges that had broken their tows – we eventually collected them within sight of the enemy held French coast at Cherbourg Peninsular. Then a bit more fetching and carrying in the sea-lanes and we were sent to HMS Boscawen the base at Portland Bill to help provide around the clock ASDIC screen for the ‘Black Prince’ and other large units of the American Fleet in their temporary base in Weymouth Roads. It was a monotonous task with one other patrol boat, backwards and the forwards round the clock across the bay. I was almost glad when we were ordered to Tilbury where the old ‘Walnut’ was to be converted to a ‘Dan-Buoy-Layer’ to help clear the extensive minefields in the Channel and the North Sea. – It seemed obvious that the War in Europe was almost over now that we had secured a bridgehead in France but the Germans had another shock in store during our passage through the Channel – we had a marvellous view of Hitler’s V1’s or Doodlebugs [Note 12] heading low over the water and destined no doubt for London. All the ack-ack guns were firing on them from every ship and it wasn’t long before the Spitfires and other fighters were hot on their trail but we didn’t actually see any shot down!.

Germans landing at Gravesend – as prisoners

We duly arrived in Tilbury and on going over on the ferry to draw stores at Gravesend I saw thousands of German prisoners of war being landed at Gravesend. This became a daily sight in Gravesend they looked a very sorry sight indeed and a poor advert for the ‘Master Race’ from the Fortress of Europe. Large Troop Ships were also docking regularly bringing our lads home to Blighty – in fact I got word that my brother John was on his way home after 2 ½ years in Trincomalee, Ceylon and we did manage a night out together shortly after he arrived. He made me laugh when he described the crowded troopship calling at Bombay – the heat was so intense John said and then a whole batch of time expired soldiers came aboard and flopped on the deck. As the great ship pulled away a loud clear voice came on the Tannoy [Note 13] “Gentlemen you are now witnessing the ninth wonder of the modern world – Bombay from the arse end of a troop ship”!!

Promoted Regulating Petty Officer

Another call came for former policemen to transfer to the Regulating Branch and this time my request to transfer went through and I was back in Barracks within a few days. Then it was drilling with a squad for a couple of weeks until we passed out as Leading Seamen then a further 4 weeks course learning all about Naval Law and Practice and then in front of the commander to be rated up as Temporary Acting Regulating Petty Officer and I was posted to Covehithe in Suffolk a Shore Base (transit camp) for Naval Stokers but within six weeks I was demobbed under Class “B” to return to the Police and I was demobbed on 5th September, 1945.

Pride in service with the Navy

I have always looked back with a great deal of pride on the few years I served in the Royal Navy and especially the time I spent on a humble minesweeper where I made many friends. I’m sure the experience broadened my outlook quite a lot and was to be of immense help to me in the years ahead in the police.

Notes:

[1] Windlass - a type of winch used especially on ships to hoist anchors and haul on mooring lines and, especially formerly, to lower buckets into and hoist them up from wells.

[2] Hawsepipe - the pipe passing through the bow section of a ship that the anchor chain passes through.

[4] Collier ship - a bulk cargo ship designed to carry coal, especially for naval use by coal-fired warships.

[ 6 ] At the start of WWII, the Germans developed a new magnetic trigger for mines based on the mine's sensitivity to the magnetic field of a ship passing nearby. Degaussing is a process in which systems of electrical cables are installed around the circumference of a ship's hull allowing a measured electrical current to pass through these cables to cancel out a ship's magnetic field. Deguassing, when done correctly, is said to make a ship "invisible" to the sensors of magnetic mines.

[7] Ack-ack was an abbreviation of anti-aircraft artillery (from the spelling alphabet used by the British for voice transmissions of “AA”). It was a nickname for anti-aircraft guns.

[9] E-boat = A German torpedo boat used in World War II. An E-boat was the Western Allies' designation for the fast attack craft (German: Schnellboot, or S-Boot, meaning "fast boat") of the Kriegsmarine during World War II; E-boat could refer to a patrol craft from an armed motorboat to a large Torpedoboot. On the other hand, you may have heard of a U-boat which was a German submarine used in World War I or World War II. U-boat is an anglicised version of the German word U-Boot [ˈuːboːt], a shortening of Unterseeboot, literally "undersea boat". While the German term refers to any submarine, the English one (in common with several other languages) refers specifically to military submarines operated by Germany, particularly in the First and Second World Wars.

[10] Mulberry harbours were floating articial harbours designed and constructed by British military engineers during World War II.

[11] Demobbed - is informal British meaning to discharge a person from the armed forces; demobilize.

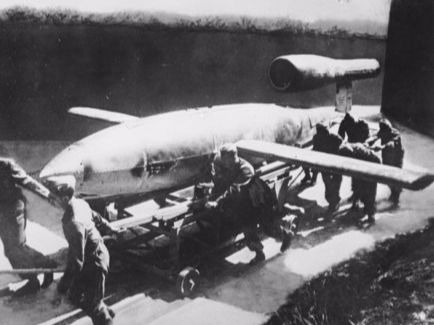

[12] A doodlebug, also known as buzz bombs, were V-1 were flying bombs. In Germany they were known as as Kirschkern (cherry stone) or Maikäfer (maybug). See image below.

[13] Tanoy Ltd. is a British manufacturer of loudspeakers and public-address sytems . The name Tannoy is a syllabic abbreviation of tantalum alloy, which was the material used in a type of electrolytic rectifier developed by the company. The brand was trademarked in 1932. Tanoy became a household name as a result of supplying PA systems to the armed forces during World War II, and to Butlins and Pontins holiday camps after the war. Identification being such because the company logo name was prominently shown on the speaker grills.

[3] A .5-inch Mk. III, four-gun anti-aircraft mount and its crew on the cruiser HMS London in 1941 - Photo Source: By Parnall, C H (Lt), Royal Navy official photographer - This is photograph A 5901 from the collections of the Imperial War Museums (collection no. 4700-01), Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=3072978

[6] Oropesa Minesweeping Float - Photo source: By Camera Operator: DON S. MONTGOMERY - ID:DN-ST-83-11254 / National Archive# NN33300514 2005-06-30 / Service Depicted: Navy, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=2995216

[8] A Royal Navy Oerlikon gunner at his gun mount aboard the Dido-class cruiser in 1942. Photo source: by Zimmerman, E A (Lt), Royal Navy official photographer - This is photograph A 9575 from the collections of the Imperial War Museums (collection no. 4700-01), Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=2915163

[12] A German crew rolls out a V-1 flying bomb. Photo source: By Bundesarchiv, Bild 146-1973-029A-24A / Lysiak / CC-BY-SA 3.0, CC BY-SA 3.0 de, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=5482719

Courtesy of the Guildford BSAC HMT Pine Project - Project Report April 2012-May 2013 by Members of the Guildford Branch of the British Sub Aqua Club. Author: Anne-Marie Mason, Diving Officer, Guildford BSAC. © GBSAC 2013. Used with permission.

As part of a dive project by the Guildford Branch of the British Sub Aqua Club, the club organized a dive to view the wreck of the HMT Pine. Tom McCabe mentions the Pine incident in his writings above. The Walnut ship was part of the W-243 convoy where the Pine was torpedoed. It could just as easily have been the Walnut that was hit that night, changing the course of history for her transport of human cargo only four years later.

The following is part of the Guildford BSAC's research into the event which they have generously allowed us to reprint and share:

"On 31st January 1944, HMT Pine was part of the escort to the Channel convoy, sweeping for mines ahead of the convoy along with two other Tree Class Trawlers. Around lunchtime on Sunday, Pine picked up a convoy off Southend and proceeded enroute to Portsmouth. Convoy Cw-243 consisted of 10 merchant vessels and 7 escorts detained for St Helen’s Road from Southend. It comprised HMS Haslemere, HMS Albrighton, HMT Rehearo, HMT Lorraine, HMT Blackthorn, HMT Walnut and HMT Pine. The merchant vessels including among others the Caleb Sprague, Emerald Balduin, Ara and Jernland.

The convoy left Southend on the 30th January 1944 bound for St. Helens Roads. It would be passing through the infamous E-boat alley, a popular hunting ground of German fast attack boats out of Calais. The first day passed uneventfully as the convoy steamed at 7 knots along the south coast. Late into the day a Sunderland of coastal command spotted a U-boat on the surface but it soon submerged and nothing more was reported.

On into the night the convoy pressed on, slowly passing Beachy Head. The three Tree class armed trawlers Walnut, Pine and Blackthorn were ahead of the convoy on mine-sweeping duties clearing the path for the merchant vessels behind. Leading the port column of vessels was the Fleet Auxiliary HMS Haslemere commanded by the convoy commodore. Tailing the port column of merchant vessels was HMT Lorraine and behind the starboard column HMT Rehearo, finally tailing the convoy was the destroyer HMS Albrighton.

At 0145 a radar operator on the Sussex shore spotted 10 new plots on his screen headed straight for the convoy plodding along at 7 knots. The new blips on his radar were headed for the convoy at 40 knots and it could mean only one thing. A pack of E-boats was hunting and had found the convoy. The civilian radar operator then made a fatal mistake of following procedure to the letter and went to find a senior naval officer to give him permission to make a plain language transmission to warn the convoy. All the time the Eboats closed in on the convoy.

The E-boats had laid waiting in the channel with their engines turned off and watching for the lights and listening for the transmission of the convoy proceeding down the channel. When they confirmed their target they started their engines and raced towards the convoy at 40 knots. Splitting into 2 groups they encircled the convoy and began to fire torpedoes at the advancing merchant vessels.

One group of E-boats attacked the centre of the convoy and in the ensuing melee the Caleb Sprague and The Emerald were both sank in quick succession. At this time the call of ‘action stations’ had passed along the escorts and HMS Albrighton charged in between the lines of merchant vessels and engaged the E-boats as best she could.

The second group of E-boats had made their way around the front of the convoy and were now attempting to engage the convoy from the coastal side. It was at this time that HMT Pine was torpedoed by S142 commanded by Oberlutenant zur See Hinrich Ahrens. The torpedo hit HMT Pine on the bow and blew it clean off, 10 men were instantly killed in the attack.

The E-boats seemed content with their 3 ‘kills’ and left as quickly as they had arrived. The convoy stayed on high alert and began to ‘hug the coast’ to try and avoid a further anticipated attack form the e-boats. The convoy was ordered not to slow down and make best speed towards the safety of Portsmouth, leaving the crippled HMT Pine adrift behind them." (Pages 66-67)

Note: There is an additional image of the HMS Birch and HMS Walnut practicing the A-sweep on page 130.

The Role of Armed Trawlers

Armed Trawlers played an important role in the Second World War. The start of the Second World War saw a huge rise in the industrial needs of Great Britain. Our allies and trading partners had only one way to get the raw materials into this country and that was via the sea - we are after all an island nation. Raw materials were brought in from across the globe to British ports and harbours, but they required protecting throughout their journey. This protection was afforded by merchant ship via the Royal Navy, but it left one vital link in the chain unguarded and that was the final approach to our coastline.

Initially the armed trawler was a simple and effective attempt to protect the ports and harbours of the country. The navy quickly saw the benefit in converting fishing trawlers to protection duties around the approaches to our major ports; after all who better to police the local area than the local fishermen? Many trawlers were quickly converted to both antisubmarine and mine-sweeping duties and crewed with the experience of the local fishing fleets.

This worked well for the fishermen as the boats they knew how best to handle were the very fishing boats being converted for war. Those self-same boats were highly seaworthy and able to put out to sea in all weathers. They became the work horse of coastal protection with many and varied roles, from the opening and closing of boom gates, barrage balloon tethers, anti-submarine warfare and sweeping the approaches for drifting submerged mines.

The navy initially classified the requisitioned trawlers’ by manufacturer and 3 classes of requisitioned trawler came about; they were the Mersey, Strath and Castle classes. It was only later that the navy began to commission new trawlers to be built and all subsequent classes of trawler had the same ancestry. It was the trawler Basset built in 1935 that all subsequent armed trawlers’ were based upon. There were 13 sub classes of armed trawlers, they were Basset, Tree, Dance, Shakespearian, Isles, Admiralty, Portuguese, Brazilian, Castle, Hills, Fish, Round Table and Military class, in total 250 armed trawlers were built between 1935 and 1945.

With the invasion and subsequent liberation of France, a new phase in the war emerged and the armed trawlers were suddenly called to serve in a new and unfamiliar capacity, this time as convoy protection; a role they were woefully unsuited for both in fire power and manoeuvrability. Many convoys’ plied the coastal routes and armed trawlers were called to provide protection from submarines to these convoys. The slow speed of the trawlers meant that often should a trawler be called away to investigate a submarine sighting or engage the enemy of any kind they would quickly drop behind the convoy and many hours would go by before the trawlers’ could return to their positions.

The German U-boat captains knew of the short comings of the trawlers and would play a cat and mouse game with the armed trawlers. The U-boats could outpace the armed trawlers on the surface so would let themselves be sighted before turning and trying to outrun the armed trawlers to get to a position enabling them to engage the allied convoys. (Page 62-63)

Armed trawlers were stationed in small fleets anywhere the admiralty thought they were required. Many stationed around the coast of Britain, in Shetland, Plymouth, Portland, Portsmouth and Rosyth. A number of armed trawlers were stationed further afield from Iceland through Gibraltar and the Mediterranean to the Azores and South Africa. The humble armed trawler made her presence felt across the globe. (Page 64).